Ancient Chinese society used rites to regulate the form and scale of buildings; it was the requirements of rites that had created ritual structures like altars, temples, and shrines. The formation and development of these structures were considerably influenced by people’s reverence toward the gods in the altars, temples, and shrines. Such ritual architectures come in two categories: for gods of nature and for gods of humanity. Different gods receive different sacrifices and offerings, and the form and scale of their buildings differ with one another according to the statuses of their deity.

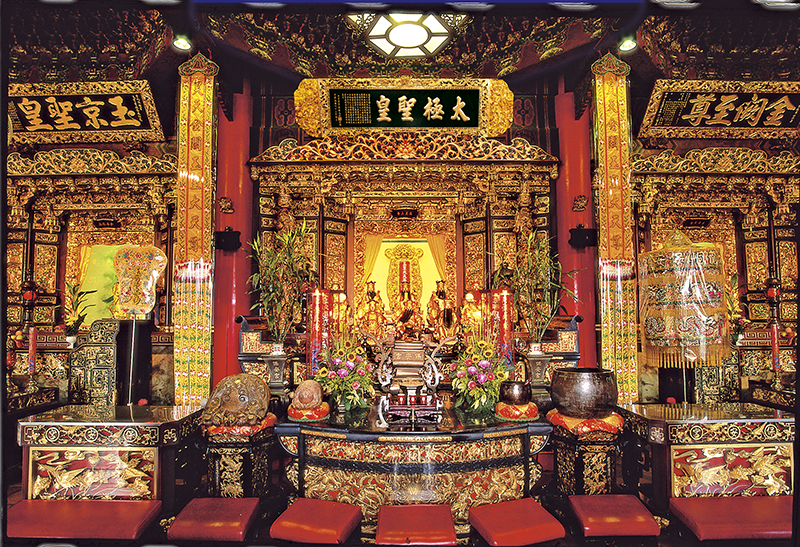

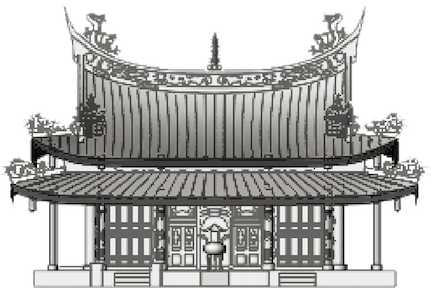

The presiding deity that Baoan Temple enshrines is Baosheng Dadi. Being a great Taoist saint of the Song dynasty, he was bestowed an emperor’s title and therefore entitled to the rites befitting an emperor. This 3,000-ping temple ground marks the nation’s largest temple for Baosheng Dadi. The temple is oriented to the south. The main structure in the middle includes Sanchuan Dian (the triple gate Front Hall), the Main Hall, and the Rear Hall. On the sides are the East/West Wing and the Bell/Drum Tower. All combined, they form a complete, three-hall “回” shape. The Main Hall is the tallest; next in sequence are the Rear Hall, the Front Hall, and the East/West Wing. Such hierarchy is in line with Confucian rituals and Taoist formations. At the courtyard pond, there sits a Buddhist swastika-shaped bridge. Adding the screen wall built in 1961 to the mix, we have an embodiment of feng shui: “backup in the rear, guards on both sides, and a screen in the front.”

Baoan Temple’s architectural style also reflects early settlers’ ancestral backgrounds. For instance, the rooftop adopts the traditional Sanchuan (triple gate) wooden structure; the roof ridge belongs to the southern Fujian style; the floor and wall surface are covered with wide, thin red bricks and tiles. In Sanchuan Dian and the Main Hall, the dragon-head components protruding from the hanging decorative items represent the style from the Tong’an, Zhangzhou, and Quanzhou regions. These architectural features are all historically significant. The temple structure also displays delicate architectural work of arts, such as woodcarvings, stone carvings, colored drawings, clay sculptures, and chien-nien (cut and glue) figurines. Both arts and religion can inspire people to become reverent.

The presiding deity that Baoan Temple enshrines is Baosheng Dadi. Being a great Taoist saint of the Song dynasty, he was bestowed an emperor’s title and therefore entitled to the rites befitting an emperor. This 3,000-ping temple ground marks the nation’s largest temple for Baosheng Dadi. The temple is oriented to the south. The main structure in the middle includes Sanchuan Dian (the triple gate Front Hall), the Main Hall, and the Rear Hall. On the sides are the East/West Wing and the Bell/Drum Tower. All combined, they form a complete, three-hall “回” shape. The Main Hall is the tallest; next in sequence are the Rear Hall, the Front Hall, and the East/West Wing. Such hierarchy is in line with Confucian rituals and Taoist formations. At the courtyard pond, there sits a Buddhist swastika-shaped bridge. Adding the screen wall built in 1961 to the mix, we have an embodiment of feng shui: “backup in the rear, guards on both sides, and a screen in the front.”

Baoan Temple’s architectural style also reflects early settlers’ ancestral backgrounds. For instance, the rooftop adopts the traditional Sanchuan (triple gate) wooden structure; the roof ridge belongs to the southern Fujian style; the floor and wall surface are covered with wide, thin red bricks and tiles. In Sanchuan Dian and the Main Hall, the dragon-head components protruding from the hanging decorative items represent the style from the Tong’an, Zhangzhou, and Quanzhou regions. These architectural features are all historically significant. The temple structure also displays delicate architectural work of arts, such as woodcarvings, stone carvings, colored drawings, clay sculptures, and chien-nien (cut and glue) figurines. Both arts and religion can inspire people to become reverent.

Also called the Front Hall. Its front is five-bay wide (the space between two pillars is a bay). The three middle bays are made into three doors; the left is Longmen (the dragon door), and the right is Humen (the tiger door). At the entrance of the door sit a pair of benevolent animals. There is one gate on the either side; therefore a total of eleven bays. This is a wooden structure that contains two main, cross beams and three short, decorative, hanging columns. The xieshan (gablet) double roof – along wi

Located in the center of Baoan Temple, the Main Hall is one grand-looking building. It stands alone with a front of five bays and a gablet double roof. Its rooftop features a seven-story pagoda and fine cut-and-glue figurines. This wooden structure has three cross beams and five short, decorative, hanging columns. The lofty roof occupies the majority of the field of view. As for the exterior of the building, the Main Hall is meticulously done and the style of it is rather stately. Altogether, there are 36 c

This structure features a single gable roof, with a front of nine bays. The wooden structure has three cross beams and five short, decorative, hanging columns – the same as that of the Front Hall and the Main Hall. Huge, plain cross beams and decorative hanging columns are used to present the strength and beauty of the wooden structure. The Rear Hall features graceful, wood-carved flying phoenix at the joints of beams and pillars. For tenons that come in the forms of wood-carved flowers and plants and the lion stands, the craftsmanship is also very polished.

Located on the two sides of the Main Hall, the East/West Wing feature red biscuit-fired roof tiles and white gable walls, which stand out relatively unadorned. The Bell/Drum Tower are built on top of the East/West Wing. Their roofs are of the gablet double-roof style. The square-shape towers are rather unique, comparing to the conventional hexagon towers in Taiwan. The East Wing Bell Tower and the West Wing Drum Tower feature works of masters Chen Ying-Bin and Guo Ta respectively; they present different styles for woodcarving designs and colored-drawing patterns. On the exteriors of the Bell/Drum Tower, there are horizontal tablets inscribed with “jing fa” (tolling at the sight of whale) and “tuo-feng” (lizard-skin drums roll in harmony) respectively. The network of wood brackets underneath the eaves of the Bell Tower interlinks with one another; this is highly demanding woodwork. On the seat of the bracket, there is the wood-carved “squirrel and pumpkin,” which symbolizes many offspring. Underneath the eaves of the Drum Tower, there are nicely carved “water lily” on short hanging columns, “flying phoenix” at joints of beams and pillars, and “one-footed dragon” on the wood brackets. Such are the different looks of the Bell Tower and the Drum Tower.

The rear section of Baoan Temple used to be a garden once served as shelter for the homeless. In 1980, a four-story building was erected here; Daxiong Hall and Lingxiao Hall occupy the third floor and the fourth floor respectively. The entire building was completed in 1983. It is a northern Chinese palace-style structure with gold glazed roof tiles and a double roof. The building covers about 400 pings of ground. The first floor is called Yunzhong Hall; the second floor is the library.

Decorative arts of the temple include: wood carving, stone carving, colored drawing, clay sculpture, koji pottery, and cut-and-glue figurines. These are all meaningful and educational artifacts. They come in the forms of figurines, artifacts and pictures, representing history, literature, allegory, myth, and legend stories, such as San Guo Yan Yi (Romance of the Three Kingdoms), Feng Shen Yan Yi (Romance of Heroes and Gods), as well as official historiography such as Han Shu (History of the Han Dynasty), Shi Ji (the Historical Records), etc. Other symbolisms come in homonyms and images. For instance, four bats stand for “bestowing fortune.” A gold/silver ingot means “treasure.” A vase is for “safe and well.” Crab shell wishes for “passing the entrance examination.” A gourd represents its homonym “happiness and wealth.” Flag, ball, spear, and chime stone stand for homonyms “pray, beg, auspicious, celebration.” Lute, chess, book, and painting symbolize “a family of scholars.”

On both sides of Baoan Temple’s Sanchuan Dian, there are stone carvings of Longqiang (the dragon wall) and Hubi (the tiger wall). This is based on the traditional concept of “green dragon on the left, white tiger on the right”. On the dragon wall, there carved the diagram of a sky dragon competing for a pearl ball with a water dragon in between clouds and sea waves. On the tiger wall, there carved a tigress playing with her cub underneath tree twigs in the breeze. The setting of cloud and wind is in line with the ancient saying of “cloud comes with the dragon; wind comes with the tiger,” as can be found in the classic Yi Jing (Book of Changes). On the stone walls next to the main gate, there are inscriptions of “gift of grace onto people and all” and “good virtues throughout the world” at the top panels. The mid-section of the walls sees a square window, where four one-footed dragons occupy its four sides. The center of the window is inscribed “the Taoist maiden of longevity.” The skirt section of the stone wall is carved with the auspicious qilin (Chinese unicorns). The wall is then completed with a footing section.

On both sides of Baoan Temple’s main gate stand two stone lions; one male and one female. Usually, the female lion is to have her mouth shut and the male’s mouth open. Legend has it that the craftsman made a mistake by leaving the lioness’s mouth open; and for this breach of the rule he received pay-cut. The make-up of these two stone lions is somewhat different from conventional ones. With huge eyeballs, big tails, curly hairs, wide-open mouths, chipped horns, and flat heads, this is what ancient people called di niu “a cow that nudges.” It is said that di (a nudging cow) is a ritual animal, and that a cow is a benevolent animal.

The dragon columns in the main room of Sanchuan Dian and the side room of the Main Hall were first built in 1804 and 1805; these are the oldest stone-carved works at Baoan Temple. The dragons are carved out of the octagon columns. The four-footed dragon has two front feet treading the water and two rear feet grabbing the cloud; it is quite a tremendous scene. This work is a representative work of mid-Ching dynasty stone-carved dragons. When the temple was renovated in 1918, a pair of twin-dragon columns, which symbolize harmony between heaven and earth, were added to the main room of the Main Hall. All non-dragon columns in Sanchuan Dian are square ones; this is contrary to the old preference of round columns. In the Main Hall, stone columns’ shapes come in square, hexagon, and octagon; bases of the columns are carved in three shapes: circle, square, and diamond. Such decorative arts are rarely seen in other temples. The flower-bird columns in the main room of the Rear Hall were done in the 1917 renovation. Peony and other flowers, sparrows and other birds all display their beautiful forms. These are indeed of special artistic style.

On the walls of Baoan Temple’s east and west gates, there are windows of book scrolls and bamboo nodes. The stone window frames are carved into book scrolls; within the frames there are stone-carved bamboo plants. Odd number of bamboos stands for yang, even number of bamboos stands for yin; such is for the harmony between yin and yang.

In Baoan Temple’s Sanchuan Dian, there are clay-sculpted historical stories and figurines, which can be seen at the top edge of the wall underneath the front and rear double eaves, and at the top edge of the wall above the east and west gates. These works are also the results of competitions. For the east gate, Hong Kun-Fu did the Sweet Dew Temple; for the west gate, Chen Dou-Sheng did the Phoenix Pavilion. Clay sculptures and koji pottery works on the doors and windows of the East/West Wing come in different forms and patterns of decoration: paint scrolls, book scrolls, banners, pomegranates, plantain leaves, bergamot gourds, and pumpkins. The cut-and-glue figurines and clay sculptures on the top edge of the wall underneath the double eaves of the Main Hall are done by Chen Dou-Sheng; the themes are mainly works of art and historical story figures. The dragon-tiger koji pottery pieces on the inner wall of the Main Hall are rather large in size. They were first molded and kiln-fired in small pieces, and then assembled with the signature of Hong Kun-Fu from Lujiang. As for the dragon-tiger koji pottery pieces on the inner wall of the Rear Hall, their composition and style are quite different from those of Hong Kun-Fu’s on the inner wall of the Main Hall; these were done by Su Zong-Tan from the Quanzhou, Huizhou, and Luojiang region. The various cut-and-glue figurines and koji pottery works which scatter on the roof ridges, eaves, and top edge of walls tend to be very colorful and full of storylines. Each piece was meticulously carved out and very life-like; their presence has added characteristics to the temple structure.

Woodcarvings at Baoan Temple’s Sanchuan Dian were the competing works of masters Chen Ying-Bin and Guo Ta for the 1917 renovation. Their works can be found on the panels that support the cross beams, at joints of beams and pillars, and on decorative hanging columns. Their subjects include: “Zhao Yun comes to the rescue of his lord”, “Kong Ming cleverly upsets Zhou Yu”, “Cao Cao composes a poem at a Yangtze River banquet”, “Xue Ren-Gui uses tricks to attack the Sky Ridge”, “King Cheng Tang retains the service of Yi Yin”, “Yao retains Shun”, “Wu kingdom wipes out Chu kingdom”, “Liu Bang enters Xiangyang first”, “Hua Mulan substitutes for her father as a soldier”, “Warming the wine while chatting about us hero figures”, and “Sweet Dew Temple”. Guo Ta even carved messages like “good work needs no alteration” and “good work needs no follow-up mending” on the panels that support the cross beams. The woodcarvings on the wood bracket also see the Hui’an master Zeng Yin-He’s works. On the wood brackets underneath the double-eave roof of the Main Hall, there is the work “the Eight Immortals’ big adventure in the East Sea,” which is one competing woodcarving work of Chen Ying-Bin and Guo Ta. At the time, Guo Ta carved the three characters nao dong hai for “adventure in the East Sea,” whereas Chen Ying-Bin skipped the three characters ba xian da for “the Eight Immortals’ big”. Also, on the bracket, Guo Ta carved words like “man-made lions beat real lions”. On the panels that support the cross beams, at joints of beams and pillars, on decorative hanging columns, and on the flower-patterned partition frame above the sanctuary, the themes of woodcarvings include: “Soldier bidding farewell to his mother,” “the empty town bluff,” “Cold River Pass,” and “the Eight Immortals.” As for woodcarvings at the Rear Hall, original works, on the panels that support the cross beams, at joints of beams and pillars, and on decorative hanging columns, are all preserved to this day.

The door gods on the main gate of Sanchuan Dian’s main room was originally drawn by Zhang Chang-Chun. Other drawings found on Baoan Temple’s cornices, beams, pillars, doors, and windows were mostly done by him. Door gods Qin Shu-Bao and Yu-Chi Gong on the main door were unusually vivid and therefore considered masterpieces. When Baoan Temple was re-painted and re-drawn in 1983, Liu Jia-Zheng took over the assignment. During the renovation of Sanchuan Dian, since the wood was damaged, door gods on the old front doors were salvaged and kept in Yunzhong Hall on the first floor of the Rear Building, and the new ones were created by Liu Jia-Zheng as well. On the left door of the main room, there is Qin Shu-Bao with white face, slanted eyes, and holding a mace as weapon. On the right door, there is Yu-Chi Gong, with black face, round eyes, and holding a whip as weapon. For the first side door on the dragon side, the door god is a civil official who holds an official hat and a small deer, symbolizing high ranks and great wealth. For the first side door on the tiger side, the door god is a civil official who holds formal flower arrangement and a wine cup, symbolizing additional splendor and titles. On the east and west gates, there are the four major marshal guards.

Mural painting has had a long history in China. When it was popular during the Tang dynasty, famous artists’ works could be seen in palaces and temples. In the Song dynasty, literati painting became the trend; painting on scrolls had replaced painting on walls. The latter then turned to be the specialty of folklore artisans. The corridor walls surrounding the Main Hall of Baoan Temple feature colored mural paintings. There are seven pieces with subjects as follows: “Han Xin is insulted by crawling under another person’s groin,” “the eight hammers fight Lu Wenlong at Zhuxian Town,” “Zhong Kui welcomes his sister back home,” “the Eight Immortals’ big adventure in the East Sea,” “Hua Mulan substitutes for her father as a soldier,” “Three heroes fight with Lu Bu at Hulao Pass,” and “the virtuous Mother Xu.” These unequaled masterpieces were all painted by the late national master Pan Li-Shui in 1973 for Baoan Temple.

During its 200-plus years, Baoan Temple had undergone many renovations; its decorative items also went through some changes. The renovation in Taisho Period was conducted by Zhangzhou masters Chen Ying-Bin and Guo Ta. As they staged a two-man contest, each had displayed his phenomenal craftsmanship. The end results are highly artistic and valuable, such as the woodcarvings on the panels that support the cross beams on the sides of Sanchuan Dian, the woodcarving “the Eight Immortals’ big adventures in the East Sea” on the wood bracket of the Main Halls’ double eaves, and the clay sculptures on the top edge of the wall above the east and west gates. Notably, under the influence of Western customs, Western-style buildings were carved out on the panels that support the cross beams in Sanchuan Dian; ladies in dresses and gentlemen in suits were also presented in clay sculptures. With Western culture blended into Taiwan’s traditional craftsmanship, a very special art form was thus created.

During its 200-plus years, Baoan Temple had undergone many renovations; its decorative items also went through some changes. The renovation in Taisho Period was conducted by Zhangzhou masters Chen Ying-Bin and Guo Ta. As they staged a two-man contest, each had displayed his phenomenal craftsmanship. The end results are highly artistic and valuable, such as the woodcarvings on the panels that support the cross beams on the sides of Sanchuan Dian, the woodcarving “the Eight Immortals’ big adventures in the East Sea” on the wood bracket of the Main Halls’ double eaves, and the clay sculptures on the top edge of the wall above the east and west gates. Notably, under the influence of Western customs, Western-style buildings were carved out on the panels that support the cross beams in Sanchuan Dian; ladies in dresses and gentlemen in suits were also presented in clay sculptures. With Western culture blended into Taiwan’s traditional craftsmanship, a very special art form was thus created.

大龍峒保安宮

大龍峒保安宮